“Landscape architecture is human-centric. You have to understand, first off, the users’ wants and needs, and reflect them in the design,” says Albert Cheng, who founded the international Landscape Consultant firm Cohere Design. “Design is never simply a scheme but solutions for living. Needs in real life should be taken into account.”

In the past, Cheng explains, recreational facilities, event spaces and plazas were all that was required in a large-scale residential development. But that has changed: “Now it’s more about functionality,” he notes. “For example, in Chinachem Group’s Sol City development in Yuen Long, we interlaced a human-centric landscape design with functional spaces. A range of themed green spaces, from an aerobic exercise area to a children’s playground, yoga corner and tai chi garden, offers residents an idyllic escape amid the hustle and bustle.”

Another project of note is Shinsun Yinhu Phase 2 Sales Area, on the outskirts of Hangzhou, where Cohere Design balanced aesthetics with function. With its irregularly-shaped pool, coupled with a waterside pavilion that features a curtain of falling water, the design resembles a poetic scene in ancient China where one could find a pavilion along a calm and clear lake nestled in a mountain – a perfect spot to rest after a long walk. For another landscape design project, apart from recreational facilities, Cheng deliberately added public event spaces that serve as interactive platforms for exchanges among community groups to enliven the neighbourhood.

The art of blank spaces

For every landscape design, greening is essential to the design’s success, which is no easy task. “Landscape Designers must be botany-savvy. Apart from knowledge of plant species and factors that affect their growth, like light, air and growing season, you also need to meticulously mix and match to bring out the design vision. It’s really difficult,” observes Cheng.

The design concept should also give a nod to the context. Take, for example, Sunac Majestic Mansion Sales Area in Huzhou. The art of Chinese ink wash is employed throughout. At the entrance is an artistic, abstract presentation of mountains – resonating with the nearby Renhuang Mountain – in the form of a feature wall and sculptures, ingeniously bringing nature into the landscaping.

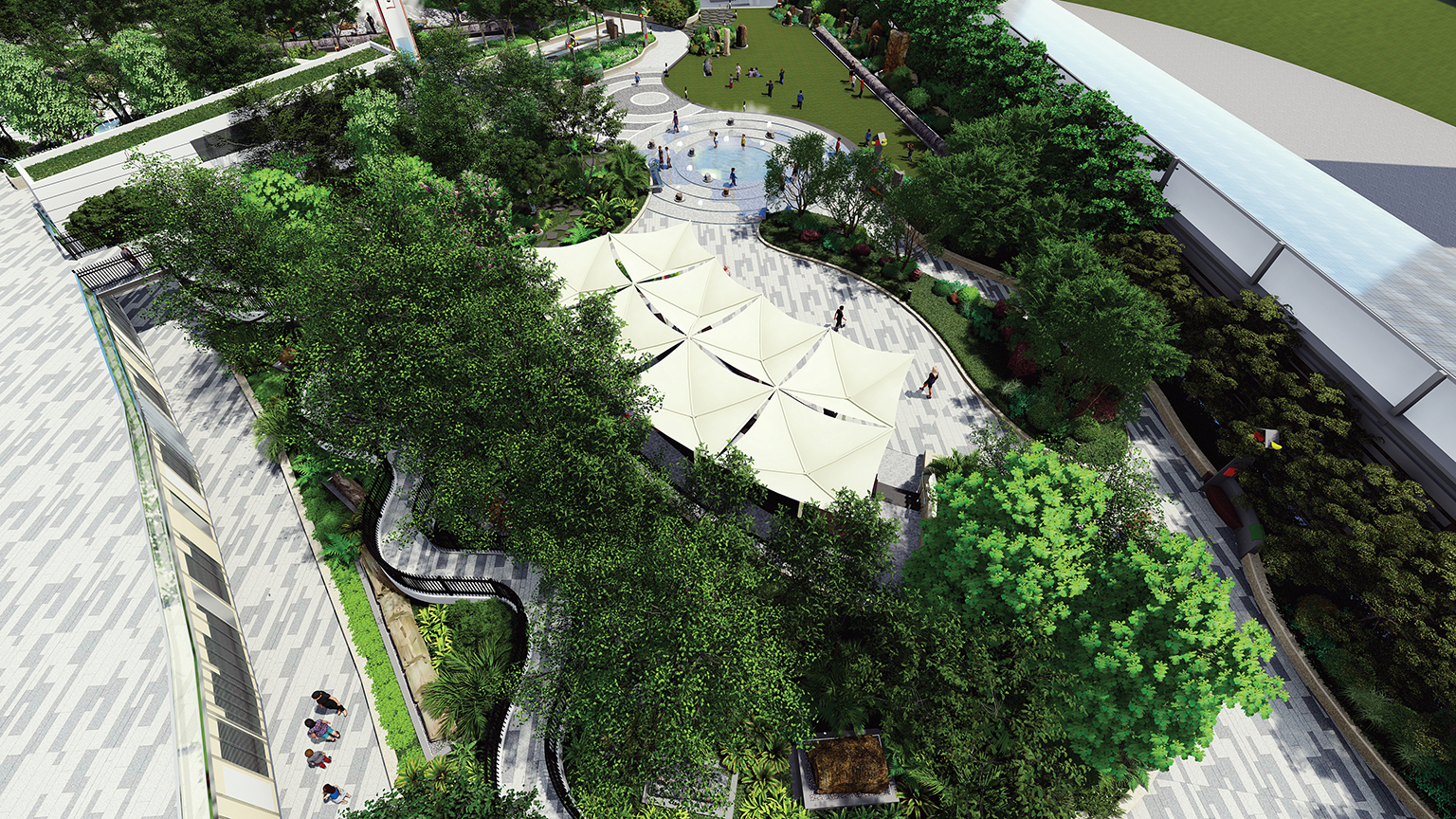

Eco-efficiency is also crucial in landscape design. In Chinachem Group’s upcoming Nina Park community space in Tsuen Wan, for example, a harvesting system will collect and filter rainwater for irrigation and other uses. The design successfully exploits natural resources, with rainwater as the sole source for irrigation, making the project highly eco-efficient.

Flexibility for future adaptation is the ultimate key to design, says Cheng. “We like to leave things ‘blank’ when we plan a space. We don’t usually fill the space all up but allow areas for future adaptation. By doing so, you don’t have to alter the space or redo the whole thing frequently, keeping it flexible for sustainable development.”

“At Nina Park, the lawn will feature a showcase of wood fossils, while a rainwater harvesting centre and amphitheatre represent spaces that are left ‘blank’,” he says. They can be easily adapted or transformed according to future needs. “Our society is fast-paced but we cannot always redevelop projects with a new design,” Cheng explains. An ageless design that moves with the times is the true epitome of sustainable development.

Internationally acclaimed